Prosperity, Depression & War

Industrial growth, economic expansion, and plenty of consumer goods gave women more purchasing power and pleasure in the 1920s. Women gained political office, but after achieving the right to vote the Women’s Movement fractured over the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The percentage of married women in the workforce doubled, though in menial jobs, while women of color had few opportunities. The media’s message about the home was ambivalent. For daughters, the young flapper was glamorized in movies starring Clara Bow who had It (sex appeal). But the modern mother, equipped with widely-advertised appliances, was expected to keep house and raise children with new efficiency.

The prosperity of the twenties contrasted with the hardships of the 1930s following the 1929 stock market crash. Farm families in the Dust Bowl, suffering from drought and crop failures, fled to California where they worked as migratory laborers. As impoverished families across America struggled, desertion rose (but not divorce, which was expensive), and family size grew smaller. Women’s jobs were largely confined to low-paying domestic labor, garment factories, and food-processing plants, all further segregated by race and ethnicity.

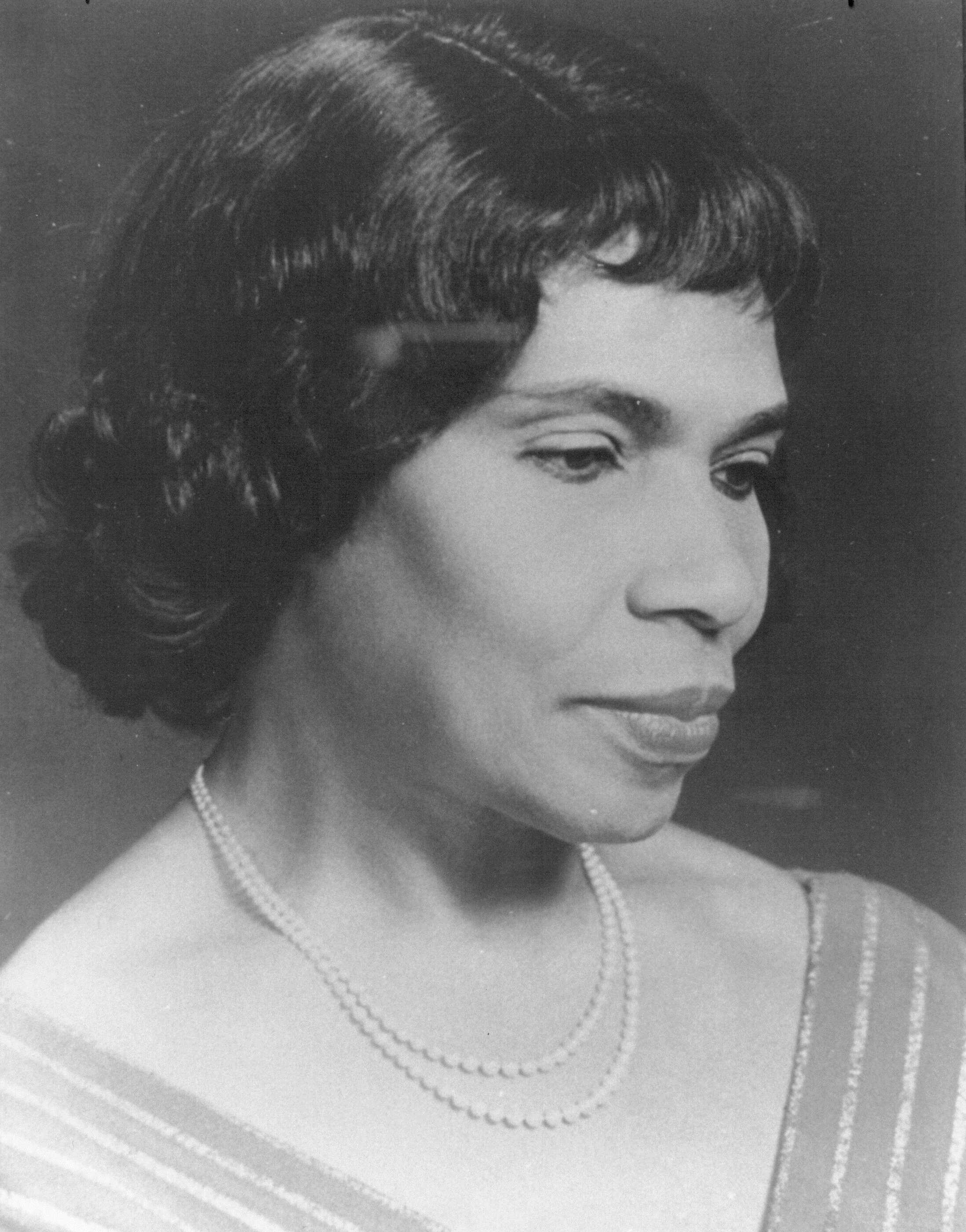

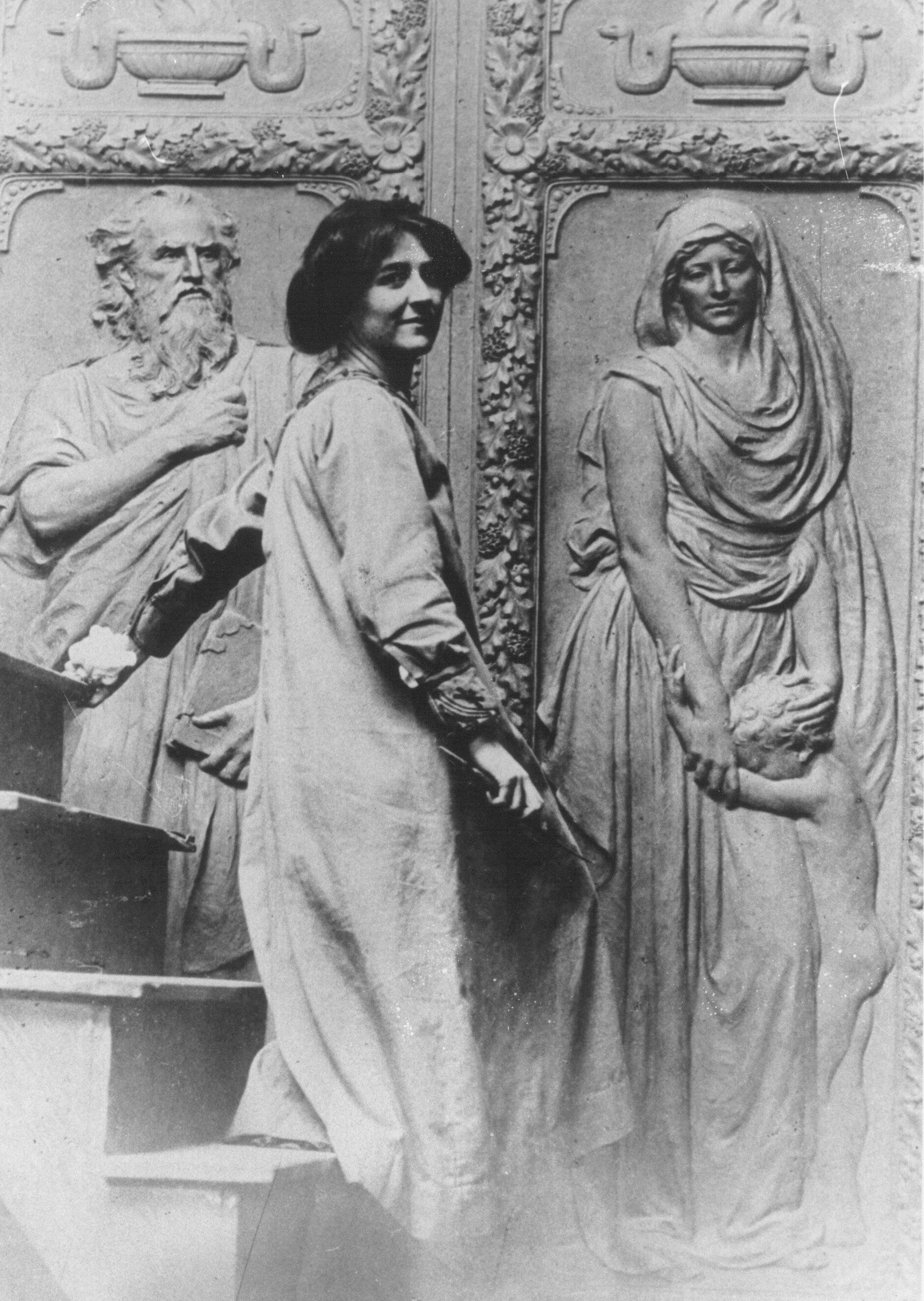

In the midst of the Great Depression, President Roosevelt, helped by wife Eleanor, brought strong leadership toward recovery with the New Deal. Professional women were included in federal projects, and work relief programs gave help to poor women. The Social Security Act of 1935 owed much to Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in the Cabinet. African-American Mary McLeod Bethune, using her executive position in the National Youth Administration, pressured the administration to provide equal pay for blacks in all programs.

World War II deeply influenced women’s lives. Sex-segregated labor diminished, as symbolized in the poster of “Rosie the Riveter.” Women were accepted into the military, though the public was concerned about the loss of femininity. Defense industries were reluctant to admit women, but as men were drafted, the resistance eroded. Older, married women provided the largest number of new workers. Black, Mexican, and Chinese women had new opportunities, but Japanese women suffered internment in camps. With demobilization, women were laid off, but many were soon back on the job. Their role still was defined in the home, but the war had increased women’s activities in the workplace.

Special thanks to Barbara E. Lacey, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of History, St. Joseph's College (Hartford, CT) for preparing these historical summaries.