Women’s Activism in Conservative Times

The Cold War in the 1950s between the Soviet Union and the United States produced fear of domestic subversion. The McCarthy Era purged suspected Communists from government, the entertainment industry, and universities, and labeled gays and lesbians as un-American security risks. General anxiety contributed to a popular conception of the family as a source of social stability, and reinforced traditional notions of women’s place at home. In 1963, Betty Friedan called this promise of fulfillment through the domestic arts the “feminine mystique,” and advocated instead that women seek personal careers.

For two decades, a burgeoning economy and a growing consumer culture had expanded the availability of jobs for women. Notable was the increase in the workforce of married women, especially middle-class white women and educated women, though they were viewed in the media as working less for a career than to assist their families with needed income or desirable amenities for the home.

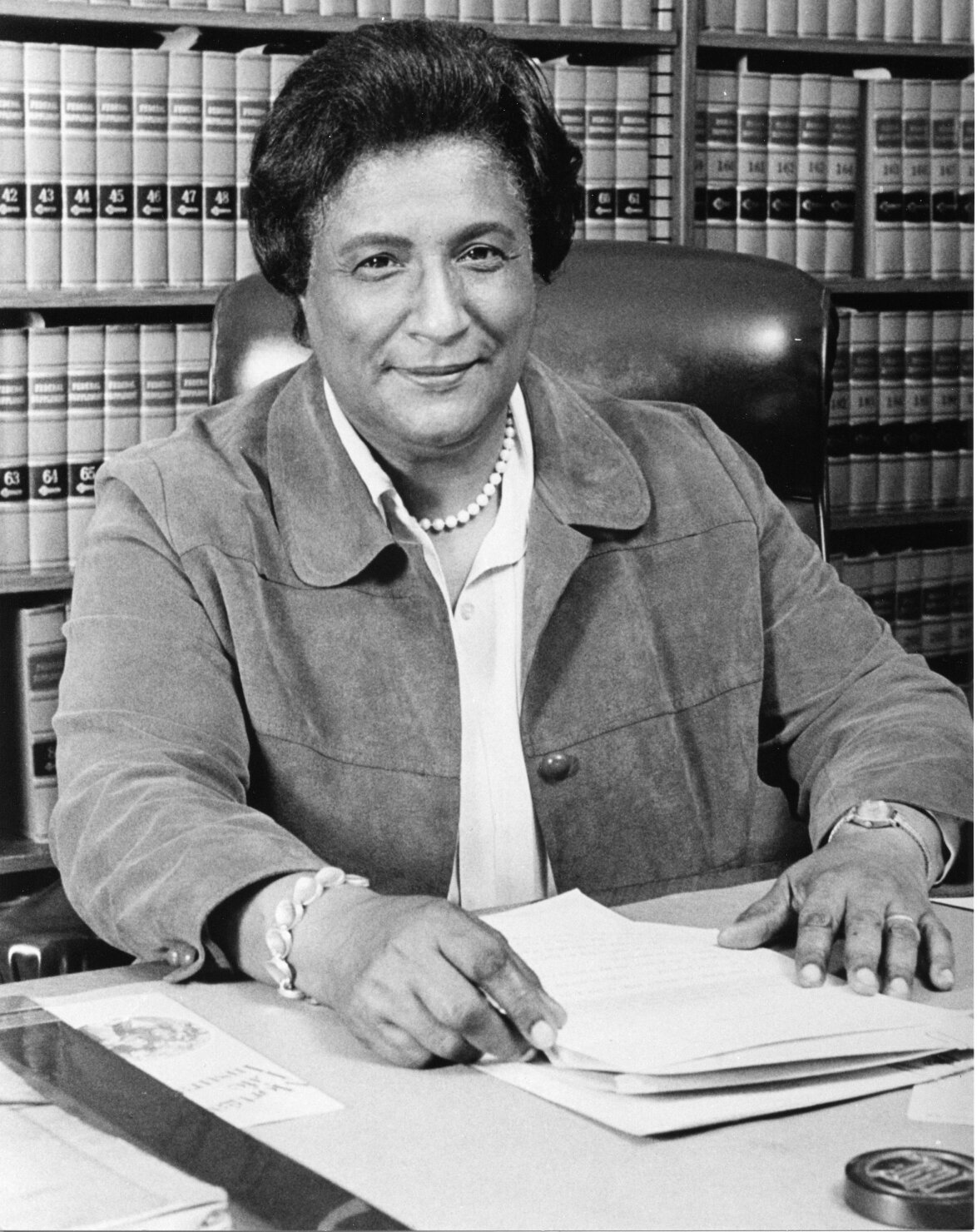

Some working-class women in labor unions challenged traditional cultural norms, such as the United Electric, Radio and Machine Workers who achieved non-discrimination clauses in local contracts. Middle-class women moderated their interest in women’s issues, promoting instead advancement through the League of Women Voters, YWCA, and the American Association of University Women. More radical women in Women Strike for Peace demonstrated against the nuclear arms race and were summoned to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1962. Many activists would join the Civil Rights Movement.

The movement against segregation following World War II dates from the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled that segregated schools are inherently unequal and thus a violation of the 14th amendment. African-Americans were given new hope, and in 1955 Rosa Parks, a black seamstress who refused to give up her seat to a white man on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, triggered a bus boycott of critical importance. Black women and white women took part in boycotts, sit-ins, demonstrations, and marches. A culminating achievement in 1965 was the Voting Rights Act pushed through by President Johnson.

Mexican-Americans in the southwest also fought to improve their life and work conditions. In 1962, Dolores Huerta, co-founder with Cesar Chavez of the United Farm Workers, played a leading role in organizing a national boycott of grapes that forced growers to sign a contract with the union.

Other ethnic groups were soon to come to America, enriching its diversity. The Immigrant and Nationality Act of 1965 established an immigration system based on family preference. Half of the new immigrants came from Mexico and Central and South America, while a quarter were from Asia. Two-thirds of the immigrants were women and children. While poverty and acculturation were issues, for many the time-honored American process of upward social mobility had begun.

Special thanks to Barbara E. Lacey, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of History, St. Joseph's College (Hartford, CT) for preparing these historical summaries.